We’re in the middle of a seismic shift in the music industry thanks to the continuing demand for immersive mixes in addition to the stereo mixes we’ve been doing for decades. I think this is a positive for the industry. It opens up opportunities to hear music in ways that were difficult or impossible before, and it demonstrates the music industry’s ability to keep pace with technological advancement.

Adapting to this shift is, however, comparatively expensive. A proper immersive mixing studio is a big investment. The question of just how much immersive music mixing work can be done on headphones comes up frequently. The accepted wisdom is always ‘don’t send out an immersive mix until it has been heard on loudspeakers.’ I believe this to be true. But simply saying that is unhelpful without going into more detail.

For context, I’ve listened to a great deal of music in great Dolby Atmos studios, and have mixed a lot of music in these studios, as well. Here are some of the drawbacks of mixing on headphones, along with some of the lesser-known benefits of mixing on headphones which I have observed. The best way to work on immersive mixes with headphones is with Audiomovers’ Binaural Renderer for Apple Music.

HEIGHT

Let’s imagine you’re working on a pop or EDM mix and you’ve already firmly established the bass and drums mostly in the Left/Center/Right speakers. Additional, lighter elements, such as an added synth part, background vocals, or percussion overdubs can be safely pushed into the height channels for excitement and added dimension. It’s unlikely you’ll make a mistake in headphones here. However, if you’re working with multiple microphones in an acoustic mix, and you have a mixture of spot microphones, room mics, or even ceiling mics at your disposal, the height channels need to be dealt with more carefully. One of my biggest Atmos mixing mistakes was during the production of a classical string quartet album. I had ceiling mics, and as I raised the level of the ceiling mics, there was a fine line between those microphones adding space, and those microphones putting a second string quartet up on the ceiling! This was nearly impossible to hear on headphones, but embarrassingly obvious on loudspeakers. Fortunately, I fixed the mistake before delivering an ADM to the record label.

Grammy-winning classical and jazz producer Silas Brown talks about the heights in a recent conversation: “I would find it very challenging to mix an Atmos release on headphones without at least being able to check it periodically on speakers. Some concerns I would have would be getting the height dimension and also the surround material balanced just right. But these raise different issues for me. When the height material is integrated well on speakers, I feel it adds tremendously to both the ‘3D’ quality and the suspension of disbelief, where the listener stops hearing a recording and starts connecting to the music. It’s not just about having energy above you, it changes the way I perceive an instrument in front of me, making it more 3-dimensional and ‘real’ for lack of a better term. But to get it just right is often a difference of a few degrees, or a very small change in ‘Size / Divergence’. I find that when judging the height relationship on headphones, I usually can’t tell when I’ve hit this narrow ‘sweet spot’ and the mixes therefore don’t have as much of this dimensionality.”

SIDE SURROUNDS

Over-filling the side surrounds is probably the most common mistake I hear in mediocre Atmos mixes. This tends to occur when starting an Atmos mix with a collection of stereo stems. All the stems start up front in the Left and Right, and the consistency between stereo and Atmos is very high. The mixer is then tempted to fill the space, and the very first thing they reach for are the Front/Rear pan knobs and pan a stereo stem halfway back into the room. In headphones, this sounds a bit more dimensional, and you might think it’s fine. I almost made this mistake recently while mixing an orchestral piece of music for a television show. The harp had a pair of close mics which made glisses move from left to right through stereo space in a very nice (somewhat clichéd) way. But panning this pair halfway back and listening on a 7.1.4 loudspeaker system made the harp sound like it was 19-feet wide and each gliss sounded like a stomach-churning side-surround roller coaster. Great Atmos mixes do fill the room. But we all got into the habit of making things (even individual instruments) sound as wide as possible in stereo. The Atmos loudspeaker-canvas is much bigger, there’s no need to make everything super-wide. Pushing the harp mics closer together and steering them more into their natural orchestral position was the answer, along with some immersive reverb. The harp was still impressive, but it was no longer racing across the room. Again, this problem was difficult to hear on headphones and obvious on loudspeakers.

Multi-platinum mixer Joseph Chudyk weighs in on this issue. Chudyk has a wide-ranging discography in country, indie rock, metal and pop. “One of the things I notice when I start a mix on headphones, and then transition to speakers, is that the location of musical elements is usually unnatural sounding and uncomfortable. The reason I’ve found for this is that these elements are pulled too far off the front wall with no solid foundation for the mix. And this is almost impossible to anticipate if you aren’t working in an Atmos-enabled room with speakers. This is something that even an Atmos mastering engineer would have difficulty remedying. Also, I have found that making the mix sound great in speakers almost ensures better translation to Apple Spatial Audio and Dolby Binaural. While working the other way around can create more issues and almost guarantees “chasing your tail” to get the mix to work on all consumer playback mediums.”

IMAGING

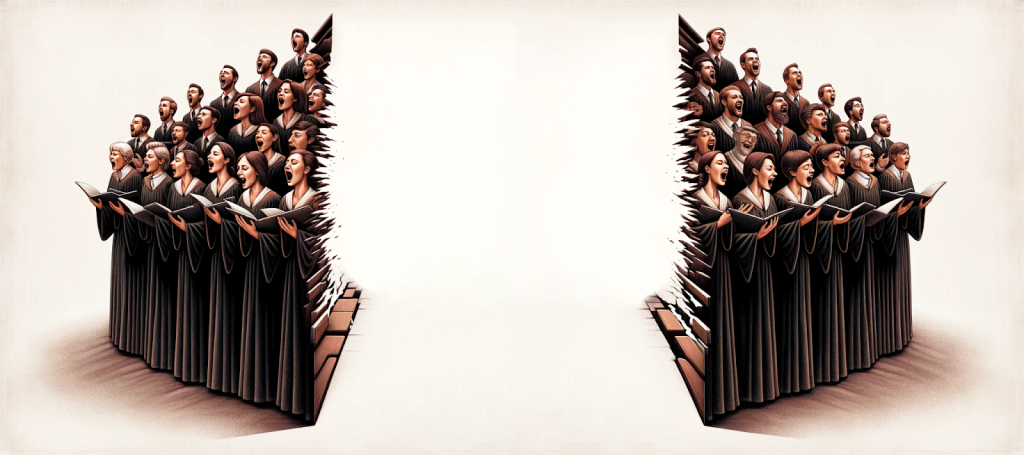

In most cases, immersive mixing is very revealing of any problems you might have in your recorded tracks. But in one notable case, conventional headphone stereo playback can reveal imaging problems that would otherwise be missed while working in immersive—drum overheads, stereo choral mics, the spaced pair in front of an orchestra—all of these techniques aim to create a coherent soundstage where the placement of instruments or voices is well-defined from left to right. When these mics are too far apart, it creates an incoherent stage. This problem is somewhat harder to hear on loudspeakers because of natural room crosstalk. But even worse, monitoring in an immersive headphone format like Apple’s Spatial Audio, and to a certain extent Dolby’s AC-4, actually glosses over the problem because those immersive headphone formats introduce artificial crosstalk between the channels. This is a case where the engineer should always check these pairs in standard stereo on headphones. The incoherence will be easily heard as a gap in the middle, and highly incoherent imaging can cause aural discomfort. The fix is usually to toe-in the mics and/or the panning until the image is consistent. And in this case, headphones win out over loudspeakers for fixing this classic problem.

SIZE

The object “size” control in the Dolby Atmos panner used to be one of the riskiest knobs to tweak while monitoring in headphones. This was because as the size value went up on an individual object, there was additional correlated signal being sent to the surrounding loudspeakers. But it was nearly impossible to hear this problem on headphones. I referred to this correlation as “dead-spots” in the Atmos canvas and rarely turned any object up over 10-12%. But to Dolby’s credit, they recently re-engineered the size algorithm with much smarter psychoacoustical filtering, and the result is now musically useful and a bit easier to hear on headphones. Regardless, less is more when it comes to using size in music mixes. If you are mixing in headphones, use size judiciously. High percentage values are probably best suited to television and film projects and less useful for music.

METERING

Meters are not all that informative when it comes to the aesthetics of mixing. But if there were one image that could sum-up a safe, and somewhat bland style of Atmos mixing, this would be it:

You might call it “stereo with decorations.” The great majority of the energy is in the L and R. The center channel (C) has just a little ambience in it, the LFE is a bit overcooked, and the rest of the channels have a few lightweight overdubs. To be fair, this distribution of energy translates well between loudspeakers and headphones, so if you are unsure of the balance of your Atmos music mix, you could use this picture as a guide. But, I find that too much adherence to this distribution underutilizes the format. Some of my favorite, more adventurous albums tend to have a more even distribution of energy around the room.

BASS, LOW FREQUENCY EFFECTS CHANNEL AND HEADPHONES

This is more anecdotal, but I feel like the quality of bass response in high-end headphones has improved considerably in the last few years. Focal, Campfire, and AirPods Max headphones reproduce frequencies I am unaccustomed to hearing without a full-range speaker or subwoofer. The headphone brands we were using in recording studios and on film sets fifteen years ago are simply not up to today’s standards. My advice is to get AirPods Max at a minimum and use them as a consumer reference. There are a startling number of young people who own these headphones. The old maxim that ‘it doesn’t matter what the mix sounds like because the kids are listening on earbuds’ no longer applies.

It’s wise to remember that Atmos is a format that does bass-management evenly anywhere in the three-dimensional Atmos canvas. What this means is that you can mix an absolutely earth-shaking record with literally nothing in the LFE channel. Some mastering engineers take this approach. But in practice, many mixers in post-production and also in hip-hop, pop, and EDM will utilize the LFE for what it is meant for:- as an effect. With this generation of headphones, it’s important to remember where and when your LFE channel will be heard. When Dolby was building the Rrenderer, they thought long and hard about the LFE and decided to include it in the binaural AC-4 render. Apple’s Spatial Audio also includes the LFE channel. But in a stereo re-render from Atmos, the LFE is dropped. That said, the majority of stereo album mixes today are done independently of the immersive mix, and the engineer has the choice of bringing that energy into the stereo channels or not.

Touching on frequency range and bass, accomplished sound supervisor John Bowen writes, “Full frequency response, crosstalk, and room feedback – all missing to some extent on headphones. Some things that you’d never notice in headphones will pop in speakers. And speakers are a must for all things bass, including LFE balancing (if you’re using it). After years of going back and forth, I feel like I’ve developed a good feel for what I’m hearing in both cases, and that’s the real goal.” Bowen has spent many hours on film and television mix stages. These stages are typically designed to reproduce very low frequencies accurately. While I am personally impressed by the new generation of headphones, I do take Bowen’s advice and carefully check the low-frequency impact of my music mixes on a bass-managed loudspeaker system with an LFE channel.

CONCLUSION

From an acoustician’s point of view, the binaural headphone reproduction of a real loudspeaker-based immersive mixing studio should be indistinguishable from the real thing. During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, I became aware of bespoke HRTF headphone models that Sony was making for its mix engineers so they could mix at home, but perceive the sound of one of their very large (and very expensive) film mixing stages while doing so. While that was a great solution to very unusual circumstances, I have yet to hear a headphone model that could replace even my modest 7.1.4 mixing studio. Grammy-winning recordist and mastering engineer Mark Donahue was describing his workflow on the phone to me, “I almost never listen to it on headphones. I will listen to it for maybe three minutes, checking a few spots – just to make sure I haven’t done something horrifically wrong.” This comment is ironic, because I’m listening to his recent recording of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 5 on headphones right now and it’s stunning. But maybe Mark’s comment is also informative. He knows that if the loudspeaker mix is right, the headphone mix will be, too.

For those of you using only a pair of headphones to mix and who were hoping to release an album in Dolby Atmos, I am sorry to say that the accepted wisdom is still true. Don’t send out an immersive mix until it has been heard on loudspeakers. But that doesn’t mean you have to hear it on loudspeakers. Buy a couple of hours of time in a Dolby Atmos studio with an engineer who shares your aesthetic and send them the ADM for feedback. This could be a mastering session, or just a critique. I guarantee it’s worth doing and it’s worth convincing your clients to spend a little extra to get this done. All of the pitfalls I’ve outlined above (and more) will be avoided, and you’ll be confident that your mix is playing well in every consumer listening environment.

Written by Nathaniel Reichman – Grammy-nominated producer and mixer with over twenty years of experience in the audio industry. He is the immersive-music mixer at Dubway Studios, a television re-recording mixer at Beatstreet NYC, and the audio producer for composer John Luther Adams. As co-founder of the new software company Immersive Machines, LLC, Nathaniel is pushing the envelope in both the art and science of Dolby Atmos™ home theater mixing.

Connect with Nathaniel – INSTAGRAM | LINKEDIN